Why Good Doctors Prescribe Bad Antibiotics

Unnecessary prescribing often stems from psychology and system friction rather than ignorance, suggesting that better systems could make the right treatment easier to choose.

We often discuss Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) as a biological problem, a Darwinian arms race between evolving bacteria and static chemistry. We track resistance genes, analyze Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) breakpoints, and develop new drug classes. But in the premiere episode of the Prescribe Responsibly podcast, Dr. Zachary Mostel, an infectious disease physician specializing in transplant medicine, pulls back the curtain on a different kind of battleground: the human mind.

The driving force behind a significant percentage of unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions isn't a lack of medical knowledge. It isn't that doctors don't know that Azithromycin doesn't kill viruses. It is a complex web of psychological pressure, systemic misalignment, and the very human fear of doing nothing.

The Pressure to "Just Do Something"

"There is cognitive dissonance when it comes to demands for antibiotics," Dr. Mostel explains during his conversation with me on Arkstone’s Prescribe Responsibly Podcast. Patients are generally aware of "superbugs" in the abstract. They watch the news. They understand that resistance is a global threat. But when they are sitting in an urgent care clinic with a sinus infection, or watching their child struggle with a cough, that global threat feels theoretical, while their discomfort feels urgent and personal.

For the clinician, this creates an impossible bind. Dr. Mostel describes the "fear of doing nothing." In a fee-for-service model, or even a value-based care model driven by patient satisfaction scores, ending a visit without a prescription can feel like a failure. It feels like the transaction is incomplete. "The doctor and the patient feel better that they gave the patient something, even if it's not indicated," Dr. Mostel notes.

This is the Do Something bias in action. Prescribing an antibiotic acts as a psychological salve for both parties. It validates the patient's illness ("You are sick enough to need medicine") and validates the physician’s role ("I have the power to help you"). However, this psychological comfort comes at a devastating biological cost. It accelerates the selection of resistant organisms, wiping out the patient's protective microbiome and priming them for future, harder-to-treat infections.

When Patients Become Customers

The Do Something bias is amplified by the commoditization of healthcare. Dr. Mostel highlights a disturbing study published in Clinical Infectious Diseases (CID) in 2024. The authors of the study went undercover as secret shoppers, utilizing direct-to-consumer telehealth companies to request antibiotics for inappropriate indications. (10.1093/cid/ciad472)

The results were stark. "It showed how effortless it was to acquire patient-selected antibiotics online," Dr. Mostel recounts. In these environments, the patient is often viewed primarily as a customer. If a customer orders a product (an antibiotic) and is refused, the business risks a negative review or a lost sale. This transactional model of medicine creates a pipeline for resistance that bypasses traditional stewardship checks and balances. It strips the physician of the gatekeeper role and replaces it with the physician as provider of goods.

Why the Right Treatment is the Hardest One to Give

Even when the will to prescribe responsibly is present, the logistics of the healthcare system often conspire against it. Dr. Mostel highlights the plight of patients with Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL) producing organisms. These bacteria have evolved mechanisms to destroy common antibiotics like penicillins and cephalosporins.

Often, the only effective treatments are intravenous (IV) carbapenems, like Meropenem. Treating an ESBL urinary tract infection (UTI) responsibly might mean sending a patient home with IV therapy. But this triggers a logistical nightmare. "The challenge of these cases is actually more logistical in real-world settings," Dr. Mostel says. "You need to coordinate between social workers, infusion companies, insurance companies, the nurse who has to come infuse the drug, and mail delivery systems."

Faced with hours of administrative burden to set up outpatient IV therapy, a busy hospitalist might be tempted to prescribe a suboptimal oral antibiotic or keep the patient in the hospital unnecessarily, increasing costs and exposure to other hospital-acquired pathogens. This is a critical insight for hospital administrators: Stewardship failure is often a workflow failure. If we make the right thing the hard thing to do, clinicians will inevitably drift toward the path of least resistance.

Three Ways to Fix the System

So, how do we break this cycle? We cannot simply demand that doctors "be braver" or that patients "stop asking." We need structural support that addresses both the psychological and logistical barriers.

1. Realigning Incentives

Hospital leadership and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) must reward stewardship as aggressively as they penalize infections. "CMS and healthcare systems need to reward stewardship efforts better for the use of narrow antibiotics," Dr. Mostel argues. If a physician takes the time to explain to a patient why they don't need antibiotics, that time should be reimbursed at a premium, recognizing the public health value of that conversation.

2. Democratizing Expertise

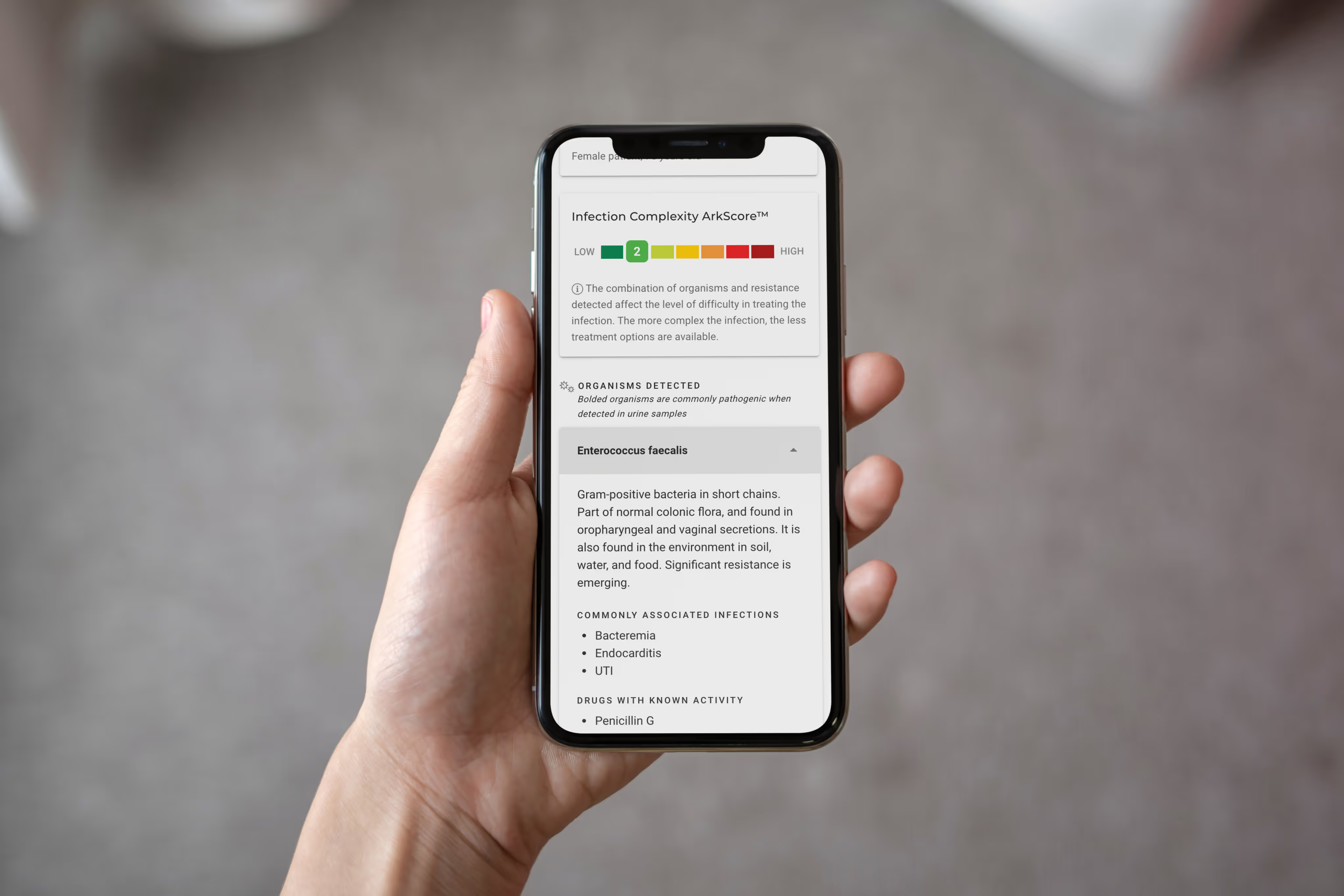

The vast majority of U.S. counties lack an infectious disease physician. Generalists are left fighting a specialist’s war. This is where Clinical Decision Support (CDS) becomes vital. Tools that can interpret complex molecular results and provide clear, actionable guidance act as a force multiplier. When a generalist receives a lab report that says, "ESBL Detected," panic often sets in. But if that same report, augmented by Artificial Intelligence (AI) like Arkstone’s OneChoice, says, "ESBL Detected. Resistance to oral beta-lactams confirmed. Preferred therapy: Ertapenem," the cognitive load is lifted.

3. Data Over Fear

When a physician has precise data, knowing not just the pathogen, but its resistance genes and the exact implied phenotype, the fear of error diminishes. Precision replaces panic. The fear of doing nothing is replaced by the confidence of doing the right thing.

Conclusion: The Future is Precise

The era of just-in-case prescribing must end. But it won't end because of lectures or posters in the breakroom. It will end when we arm clinicians with the tools to make the right decision, the easy decision. As I noted during the podcast, responsible prescribing and responsible use of antibiotics are something we all play a part in. That part includes building the infrastructure, logistical, financial, and technological aspects that make responsibility possible.

Share this article

Blogs

Latest Blogs

Stay informed with our featured blogs.

Customer Testimonials

Arkstone's solutions have transformed our patient care.

Take the Next Step, Try OneChoice®

No more guesswork. No more lookup tools. No more inaccuracies and inconsistencies. No more stopping to ask for directions.